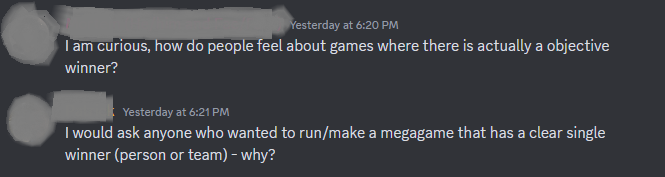

This post is spurred by some thoughts after reading some discussion in the Sydney Megagames Discord, and a couple of theory of strategy articles. As I tend to design megagames that include strategy, logistics, and the operational levels of war, these kind of serious articles often spur my brain to creative thoughts about future megagames or my current design problems.

First, some traditional wisdom from Jim Wallman:

The designer is creating an entertainment for an audience. How would you feel if, at the end of watching a movie, the movie theatre owner announced that the audience member in Row G, Seat 10 had ‘won the movie’ on points.

Victory, Defeat, and Endings, December 2016

Something that has misfired in several of my games, is that while I set goals for players, hoping that they will lead to interesting decisions and emergent play, I have found that players will often avoid goals that drive them into conflict with other players. “We all win” is an equilibrium that is attractive to players, as is “negotiate away all competition between factions so that we minimise costs”. Which is a valid choice for them to make, but means less interesting surprises and emergent gameplay down the track.

As a brief recap on goals, I like to borrow from Thucydides and have Fear (something a player wants to prevent), Interest (something the player wants to achieve), and Honour (a constraint on player behaviour). As personal goals, a player can feel like they won if they achieve them all during the game. Which can lead to another problem – completing all your goals in the first hour and then feeling disengaged from the rest of the game.

Anyway, after reading the strategy articles linked above, I am now thinking about framing game ending less in terms of victory/defeat, and more in terms of “Did you solve the problems presented to you at the start of the game?” If you make the problems sufficiently wicked, then they should keep the players busy all game. My current game design focus, Dread Crusade, has the following collective problems:

- Getting the crusaders to the Holy City (a game of logistics and battles).

- Identify the five Banes needed to kill the Dread Lord (a game of research and acquisition).

- Finding the traitors (like in Den of Wolves).

Theory of Challenge

In Bringing a Method to the Strategy Madness, Jeffrey Meiser puts goals and interests aside as being unhelpful to practitioners of strategy. In its place he offers theories of challenge, failure, and success.The theory of challenge allows you to create multiple points at which intervention can take place. The problem that the challenge presents to the players should be significant – its not something that is business as usual. If the players do nothing, then the negative effects are injected into the game by the Control team.

Theory of Success

This is the starting point for players in a game to start creating their strategies and making decisions about their actions in the game. Do you just mitigate the negative effects and move on to other challenges? Do you try and overcome the main challenge with brute force, or can you use a bit of cunning and cut it off at the roots?

One of the choices factions get to make at the start of Dread Crusade is some capability picks. Essentially this allows a faction to look at some potential problems for their journey and say “Nope, not happening to us”. Hire mercenaries and battles are easier, choose Lore and identifying Banes is faster, buy mules and supply is simpler to manage. But you cannot solve every problem this way.

Theory of Failure

This is about thinking ahead to how and why you might fail. A megagame is not just one set of decisions, it is a series of iterative and interactive decisions within the wider emergent play of the megagame.

At any rate, as the designer I need a better solution for what happens if the Crusade does not reach the Holy City – can the crusade pull an Aragorn and tempt the Dread Lord into open battle?

Complex Systems

In Strategy as Problem-Solving, Andrew Carr looks at the importance of diagnosing what your problem is before you try solving it with strategy. If you think of Watch the Skies, knowledge of what the aliens were after in one game is not necessarily true for how the aliens behave in a new game. Andrew refers often to the Cynefin framework and its four levels of order:

- Clear – problems that can be solved in a repeatable and consistent fashion through specific steps (like finding the shortest distance on a game map).

- Chaotic – situations where you must act first and analyze later (such as tactical battles).

- Complicated – unique or ordered tasks that are amenable to being solved by experts (like a Science subgame)

- Complex – the level of hard to recognise strategic problems. This encapsulates the emergent gameplay I think so many of us look for from megagames that I will quote at length here:

- Complex systems are nonlinear, meaning there is no direct relationship between inputs and outputs. Endless resources can be devoted to a task with seemingly no effect until, suddenly, there is a rapid change. Small, well-timed inputs can also have outsized effects.

- The level of order is never static. As such, the best we can hope for is “pockets of order” with patterns disposed to our interests.

- The actors within complex systems adapt and change over time based on feedback. Actors that are better able to adapt and more attuned to environmental feedback will outperform actors lacking these qualities.

- These interactions can form emergent phenomena that move the system into new patterns and dispositions.

For dealing with complex systems, the diagnostic approach involves framing, mapping, and probing the problem, so that the strategist can identify the real problem, discover future problems, and create problems for their adversaries.

Now to turn this theory into something useful for my current game design problems. I am not allergic to all trace of Victory Points, I do, however, think you need to avoid a single source of Victory Points in a megagame. Have at least three things that can represent victory, and players will make tradeoffs to match their preferences, and what is realistic to achieve with their resources in the megagame.

So for Dread Crusade the logistics, battle, and bane research elements of the game all fall within the Clear, Chaotic, and Complicated levels of play. Where I can try and make it more Complex is with:

- More emphasis on what happens after the Dread Lord is defeated, as all the various truces and deals that enable the different crusade factions to work together expire.

- Tracking territory gained, hard power army size, gold, and the more elusive soft power elements as objectives. Perhaps some kind of non-linear prestige mechanic – a rare case where I might use an exploding die roll to keep things unpredictable for the players (its easier to negotiate a deal over a fixed outcome, harder when gain/loss is uncertain).

- Doubling down on the religious faith aspects, and the tensions from the differences in religious doctrine between different crusader factions. This does require getting more than the minimum number of players for the game, which is my own complex marketing problem.

- More uses for Banes, Relics and other game tokens. Make them powerful and interesting for more factions.

- Having success create as many problems as failure by presenting immediate policy problems, such as whether collaborators should be executed, ransomed, or forgiven by the crusaders, with some zero sum elements for the different factions and faiths.

- A deliberately ambiguous set of prophecies and oracles about who can defeat the Dread Lord, with some factions (such as the Church, Inquisition, and Magi) having strongly preferred interpretations. I might reverse the “find the traitor” subgame to be much more of a “find the hero” subgame.

Great post- very thought provoking.

Cheers,

Pete.